Earlier this year, I asked my thirty-two year old daughter (who has special needs) if she and her boyfriend had any long-term commitment plans?

Lindsey had been adamant about maintaining her single status. She lived an independent life in a one-bedroom apartment less than a mile from our house. She shuffled to and from her job–at times using walking sticks to stabilize her equilibrium.

“Nick and I just like being boyfriend and girlfriend,” Lindsey answered my question. I frowned, disappointed there would be no wedding dress, wedding flowers, wedding music, or wedding pictures. I remembered the day she was born. I held her seven-pound, eight-ounce body in arms still unaware of impending mental challenges; I dreamed about prospective milestones. A wedding day was high on my fantasy list.

At sixteen months of age, Lindsey had a seizure and lost consciousness. Doctors said a febrile seizure escalated quickly. An EEG ruled out epilepsy. Lindsey’s hands started trembling. When she scooped Cheerios, most pieces slid off the spoon. We had her tested again and again. At six, OHSU finally offered a diagnosis: mildly mentally retarded (although I prefer mentally challenged or disabled)—from an unidentifiable syndrome. I was devastated. With that diagnosis, many of the dreams I held for my daughter shattered into jagged pieces, like a smashed plate glass window.

We live in Silverton, Oregon–a quaint community in the Willamette Valley. City Council approved the installation of two stoplights five years ago. Local artists have painted fourteen murals on the exterior walls of building throughout town. The most popular are Norman Rockwell’s, Four Seasons. We greet our neighbors here. We don’t honk our car horns. People look after one another. It’s been the perfect place to raise a daughter who walks with an awkward gait and whose tremors resemble a Parkinson’s patient.

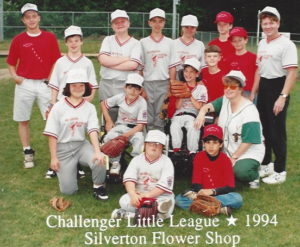

Back in the 90s, Lindsey met Nick when they played on a Challengers softball team sponsored by Norma Jean at Silverton Flower Shop. Play doesn’t accurately describe the team’s efforts because most of the players threw gloves in the air, looked for four leaf clovers, or chased one another in a game of tag. Yet Norma Jean stood on the sidelines, cheering at the top of her lungs.

Back in the 90s, Lindsey met Nick when they played on a Challengers softball team sponsored by Norma Jean at Silverton Flower Shop. Play doesn’t accurately describe the team’s efforts because most of the players threw gloves in the air, looked for four leaf clovers, or chased one another in a game of tag. Yet Norma Jean stood on the sidelines, cheering at the top of her lungs.

Nick is two years older than my daughter. He has disabilities too, but they haven’t prevented him from passing the Oregon driver’s license test. Lindsey thinks that’s cool. “I’ve always liked a man with wheels,” she told me when Nick pulled in the driveway in an oxidized, reddish-colored sedan. They attended Silverton High and were in many of the same special education classes.

For the past seven years, they’ve dated exclusively. In the beginning, Nick drove Lindsey to Walmart or Artic Circle if my daughter paid for the gas and food.

“He has vehicle expenses, Mom,” Lindsey told me, justifying her contribution. Then Nick showed up for some of our family functions; he invited Lindsey to his. Now Nick helps my daughter in and out of his car. He supports her arm when they walk across a parking lot and into a store; he holds her iced coffee so it won’t spill. They like the same kinds of movies and video games. “We both love aminals,” Lindsey said, mispronouncing the word. Lindsey says, “I love him. He’s my man. And he loves me.”

As spring ripened into summer, Lindsey’s mind must have ripened to the idea of marriage. She texted Nick and asked him if he’d marry her. Nick showed the text to his mom—who smiled and told him, “You two sure seem to be in love to me.”

On a sunny Friday afternoon in July, Lindsey and Nick came by our house. Lindsey marched into my office with an animated face, shut the door, and said in a loud, little girl voice, “You have to stay in here, Mom. Nick’s havin’ a private conversation with Dad.”

Twenty-five minutes later, no excited voices carried up the stairwell, into the hallway, or my home office. Nick talked about the weather, his car, the way he cooked meat on the grill.

John finally said, “Did you have something you came here to ask me?”

Nick took a deep breath, and blurted, “Can I marry Lindsey?”

Neither John nor I were shocked. For over a month, Lindsey had warned–prefacing each warning with, “Don’t tell anyone. It’s a secret,” that Nick planned to drop by the house for a “very impotant talk.” I chuckled, shaking my head at the mispronunciation. My husband discussed commitment, the responsibilities of marriage, and treating each other kindly, then granted Nick permission to walk Lindsey down the aisle.

That evening, Nick got down on one knee and slipped a gold, heart-shaped engagement ring around my daughter’s slender finger. They decided to get married in two years or six months or two years, “Because we don’t wanna rush into anything,” Lindsey told me, splaying her fingers to show me the delicate diamond ring.

I’d imagined a specific kind of wedding for my daughter: vineyard venue with incredible views, gorgeous wedding gown, bridesmaids, a truckload of flowers, tons of guests, a string quartet, a caterer. But Lindsey and Nick wouldn’t pin down a date. Like the majority of Lindsey and my interactions, my dreams weren’t meshing with hers. Our heads butted. I explained the difference between two years and six months and Lindsey stared at me with a blank look on her face. “We’ve only known each other for twenty years, Mom,” she said, like that explained everything.

On the next visit to Lindsey’s apartment, I walked from room to room, glaring at her empty walls. “What happened to all your pictures, Lindsey?”

“Mom!” Lindsey sounded exasperated. “I’m getting married in two years or six months or two years. I wanna be ready so I packed everything into boxes.”

My body tensed, thinking how unpleasant it would be for her to live in a white, bare-walled apartment for the next seven hundred and thirty days. Lindsey doesn’t grasp the concept of time. It’s part of her disability. She can tell time, arrives places on time, and uses a calendar, but reasoning “length of time” isn’t one of her strengths. John and I have spent hours trying to explain, re-explain, then still ended up in the same place. Lindsey has to be in a receptive mood before a successful conversation can take place. I tried to focus on her giddiness, but instead, I felt irritated with the gloomy surroundings. I fretted some of the treasured items may not have been packed properly. I gritted my teeth and stomped out the door.

A week later, on another visit to her apartment, there was a huge vacant space on the living room carpet where a custom, yellow, floral rocker and ottoman used to sit.

“I sold it to the neighbor lady,” Lindsey explained, a smile spreading across her face. “For $20.” She paused. “Since I’m moving in two years or six months or two years. I don’t need it anymore.” I clenched my teeth tight enough to crack porcelain. Knots of tension bound in my neck and shoulders. We’d paid over two hundred dollars for the two pieces. I lectured my daughter on the value of this furniture. “I asked for $50,” Lindsey said unconcerned. “But the lady only had $20.” I wondered how I’d ever make it two years until the wedding.

But Lindsey and Nick decided they couldn’t wait two years (or even six months for that matter.) They are marrying this Sunday. A small backyard wedding is planned. Invitations have been mailed. A large tent has been set up in case it rains. Lindsey picked out a simple, white satin gown with pearls and tatted lace and capped sleeves.

Her shoes are gold and glittery. She can’t decide whether to French-braid her hair or wear it down so it cascades over her shoulders. She and Nick have decided not to have attendants.

A few weeks ago, I drove her to Target so she could register for her bridal shower. The registry looks different than many brides-to-be. In addition to a few kitchen gadgets, some bath and kitchen towels, Lindsey registered for cat food and cat liter designed for “multiple cats” since she owns Sally and Cuddles. “It’s what we want,” she said when I questioned these selections. “But we’ll like anything.”

We ordered the wedding flowers from Silverton Flower Shop. Lindsey told Norma Jean that she wanted a bouquet with light pink and dark pink and white roses. “Maybe some lavender, too,” Lindsey said. “Because I like lots of colors.” When we finished ordering, Norma Jean wouldn’t give me a bill. “It’s my gift to Lindsey,” she said. “I want to do her flowers.” My heart flooded with joy, my eyes dampened. Lindsey clapped her hands like a child, thanking Norma Jean over and over.

On October 14th, Lindsey’s dad will walk her down the aisle. Louie Armstrong’s, What A Wonderful World will play from a boom box in the background. And because the bride and groom are enormous Neil Diamond fans, they’ve selected Sweet Caroline to walk back down the aisle, hand-in-hand, after the ceremony. For some reason, it doesn’t bother the couple that the bride’s name is Lindsey Jane. They just hope the audience of family yells, “Bah! Bah! Bah!” and “So good! So good! So good!” at all the appropriate times.

Tomorrow, a long, sought-after dream—adjusted to fit my daughter’s wishes—will come true for my special girl (and for me).

My first book, Loving Lindsey: Raising a Daughter with Special Needs will be out September 26, 2017. If you would like to learn more, click here.

My first book, Loving Lindsey: Raising a Daughter with Special Needs will be out September 26, 2017. If you would like to learn more, click here.

Every month, one or two organizations that do great things for people with special needs will be featured here. If you would like to support the developmentally disabled, please check these out.

Albertina Kerr helps children, adults and families in Oregon with mental health challenges and developmental disabilities, empowering them to lead fuller, self-determined lives. They were recently named Oregon’s 2nd most admired non-profit organization. If you would like to learn more about their services, volunteering, or donating, please click on above link.

Special Olympics services 4 million athletes worldwide with developmental disabilities. If you would like to learn more about how you might support this organization, please click on above link.